SLAPP'd Episode 5: Documents undermine pipeline company's claims about sacred sites

Please consider a paid subscription so I can keep doing this work in a flailing media economy.

This week Drilled published episode 5 of SLAPP’d – it’s the climax of the podcast series I’ve been reporting and hosting – and a juicy one for sure. This episode revealed to me what divide and conquer by the fossil fuel industry really looks like. And it made me realize that how little protection exists in the U.S. for Indigenous religious sites.

Background: On the Friday before Labor Day 2016, a tribal elder and expert in sacred sites named Tim Mentz identified a number of sacred places and burial sites that he asserted would be desecrated if bulldozers cleared the area for the Dakota Access Pipeline. The sites were made up of stones arranged in patterns and used for ceremonies and other purposes. The stones’ locations were filed with a North Dakota court – part of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s legal effort to halt the pipeline.

The very next day – the Saturday of a holiday weekend – the pipeline company moved their bulldozers around 15 miles to that exact area and began bulldozing, and they brought security dogs. Amy Goodman from Democracy Now! caught the dogs on tape lunging at people who were attempting to protect the sacred sites from the bulldozers. That video footage of the dogs went viral, and the Standing Rock movement exploded in popularity.

Then, about a year later, after the oil was flowing, Energy Transfer filed its big lawsuit claiming that Greenpeace was driving the Standing Rock movement, rather than Indigenous people. But the company ALSO claimed that Greenpeace committed defamation by stating that Energy Transfer deliberately desecrated sacred sites that day in 2016. That assertion didn’t originate with Greenpeace – it originated with Standing Rock leaders. This was a sideways attack on the Indigenous nation.

As I reported out what was happening with the defamation claim, I uncovered the details of a settlement proposal, where Energy Transfer pressured Greenpeace to throw the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe under the bus. (To hear more about that, you should absolutely listen to the episode.) I also found a bunch of juicy documents that seem to conflict with some of the things that Energy Transfer had been saying in court.

I've compiled some highlights from the docs – you could read them now, or you could peruse them after you listen to the episode.

Claim: There couldn’t have been sacred sites in the area, because a project called the Northern Border pipeline had been built there in the 1980s, and anything that was there would have been destroyed back then.

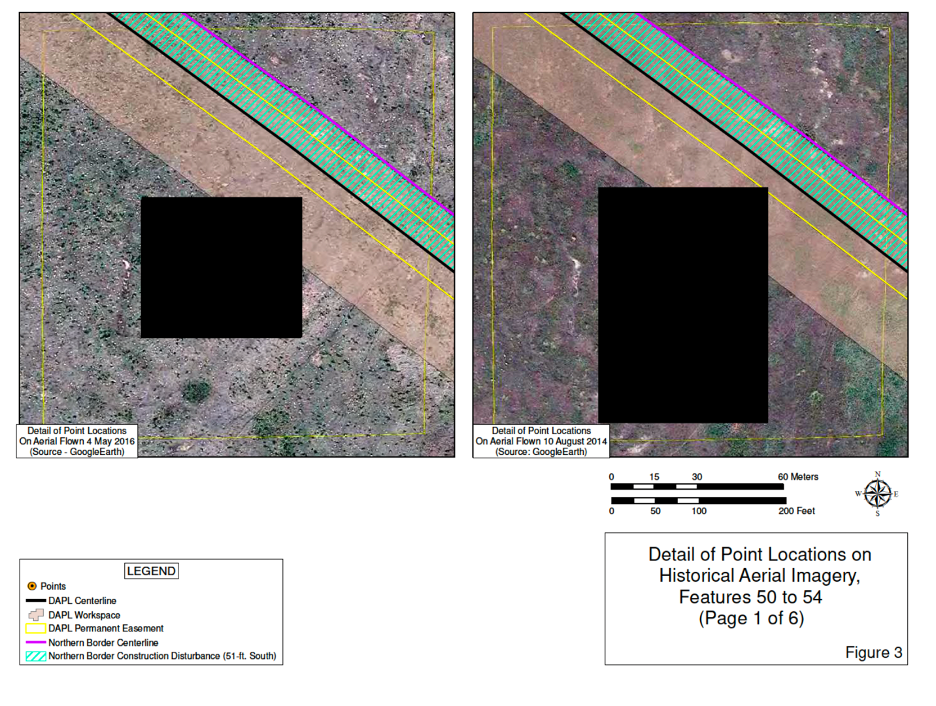

What the documents say: An archaeology company contracted by Energy Transfer drew maps of the area previously disturbed by the Northern Border pipeline.

The maps say that the sites identified by Tim Mentz, sit outside of that disturbed area.

The actual locations of the sacred sites are redacted, but you can see they do not overlap with the blue stripey part – which is the part disturbed by Northern Border construction.

Source: Contract archaeology investigation

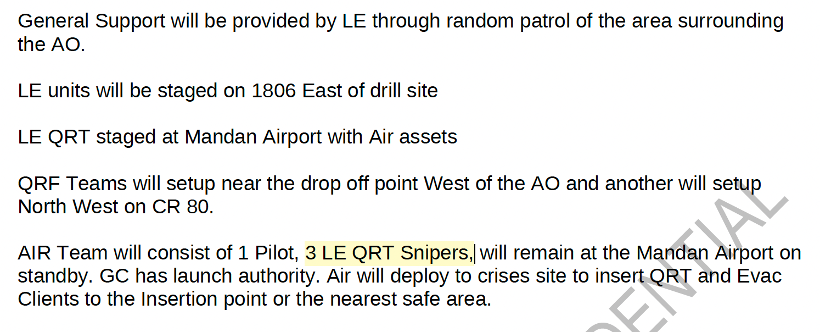

Claim: Energy Transfer had planned at least a week in advance to advance the bulldozers out of order, and law enforcement was notified of the plan. In other words, the bulldozing in that area, on that day, was not because of the identification of sacred sites.

What the documents say: Energy Transfer did send law enforcement a construction schedule, a few days before the bulldozing – but that schedule said they wouldn’t arrive to the area of the sacred sites until after September 8. Instead, they showed up September 3.

When the local Morton County Sheriff Kyle Kirchmeier testified in court, he said he was unaware there would be construction in that area that day, and that usually he was aware of those kind of plans.

Finally, a police report I obtained via a public records request, shows that Energy Transfer contacted the dog company in the middle of the night before they bulldozed the sacred sites area — several hours after they learned of the sites from the court.

Here's from the owner of the dog company, Bob Frost of Frost Kennels.

In short, both police and private security seemed to be taken by surprise at the plan to bulldoze in that area, on that day.

Here's a bit more, from another security guard.

The documents suggests that Energy Transfer was aware that people were likely to protest if they saw bulldozing in that area. Their solution was to meet them with guard dogs.

Sources: August 30 email displayed during the trial; Kyle Kirchmeier testimony at trial; Cody Hall police report

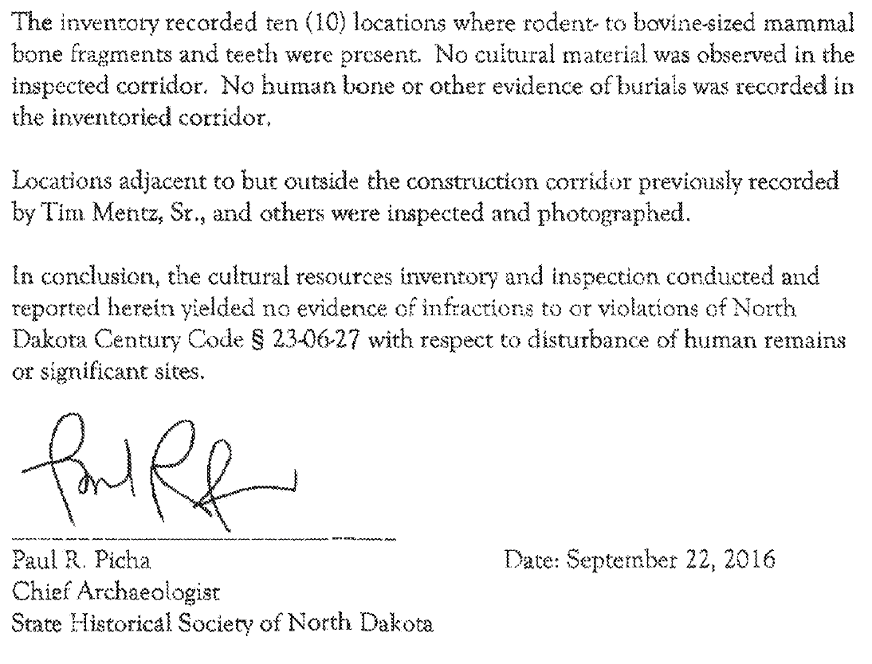

Claim: A North Dakota state archeologist didn’t find evidence of burial or archaeological sites in the area that was bulldozed – indicating there was nothing destroyed.

This is from his statement:

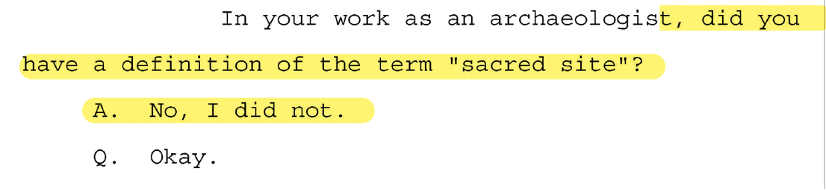

What the documents say: Both the state archaeologist and Energy Transfer’s contract archaeologist said in depositions that were never presented in trial that they didn’t actually have expertise in sacred sites. If that’s the case – then how would they or Energy Transfer – or Greenpeace for that matter – know if a site was desecrated?

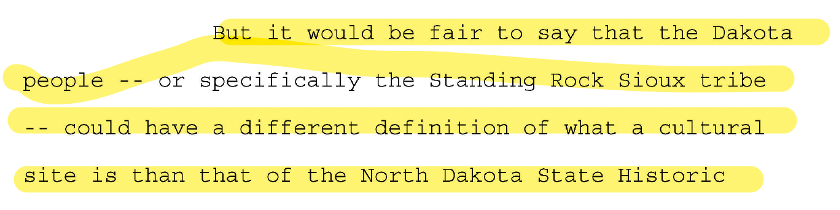

Ok so here, Jason Kovacs, a contract archeologist hired by Energy Transfer, is basically affirming to one of the lawyers that a site can be “archaeologically invisible” but still count as tribal cultural property. He’s basically saying that just because an archaeologist can’t identify a sacred site, doesn’t mean it’s not a sacred site.

This whole thing of archaeologically visible vs invisible is totally bizarro to me. An anthropologist I interviewed for the episode, Sebastian Braun, told me that archaeologists often have to see affirmative evidence of human activity for a site to be “visible.” In this case, a human man (Tim Mentz) actually told the court that these sites are important to the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe today – but that wasn't enough for the archaeologists or Energy Transfer.

Braun told me that even the lack of human bones means little in terms of whether or not these were burial sites, in part because Indigenous people of the plains tended to lay people to rest on elevated scaffolds.

All kinds of human activity takes place all over the earth without leaving behind clear evidence. So does the fact that a site is not identifiable using the narrow definitions and tools of archaeology mean that the site is not real? Even the archaeologists say no.

Here the contract archaeologist Jason Kovacs admits outright that he is not qualified to assess what is tribal cultural property or not.

In fact, he says that most of the time he has no access to a tribal perspective at all. He can’t tell what is a sacred site and what is not.

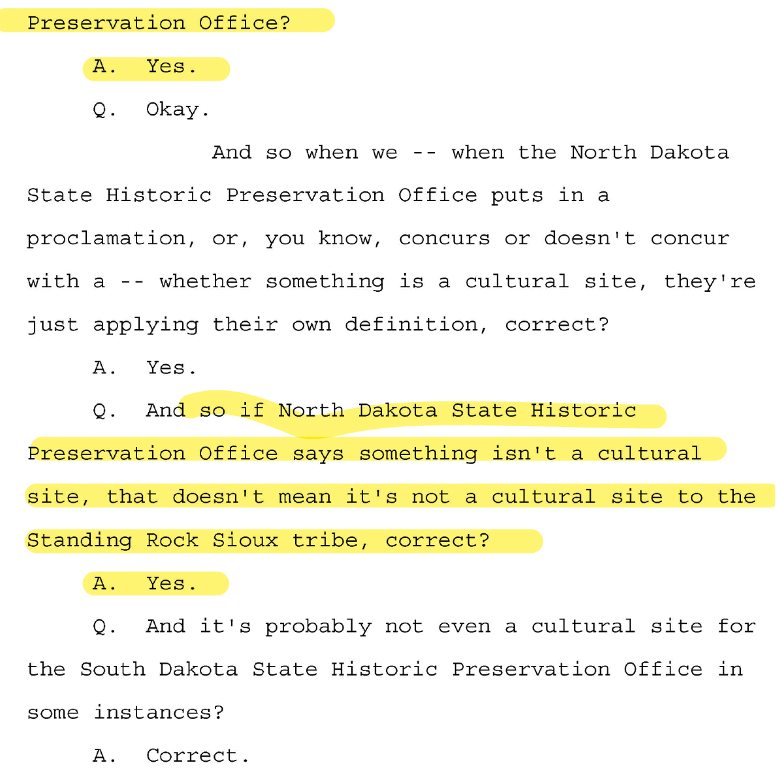

Here, the former North Dakota state archeologist, Paul Picha, talks about how North Dakota’s definition of a “cultural site” isn’t necessarily the same as the Standing Rock Sioux or any other tribal nation’s definition of a sacred site. (Which seems kinda weird to me, because why would the historically white North Dakota Historic Preservation Society know better than the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe which sites are culturally important?)

And similarly to Kovacs, Picha admits here that he doesn’t even have a definition of the term “sacred site.” So how would he know if one was desecrated?

Sources: Kovacs Deposition, Picha Deposition

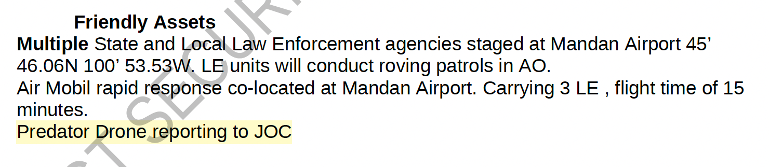

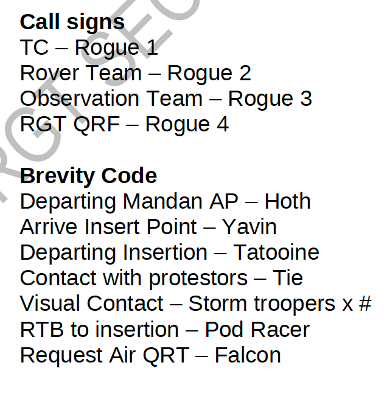

Bonus document: The day Kovacs and Picha went out to inspect the sites, Energy Transfer’s security team actually created this super elaborate security plan. They called it Operation Point Break – yes, named after that Keanu Reeves movie where he’s an undercover FBI agent going after a group of surfer/bank robbers. (Great summer viewing, btw, but skip the remake, which involves corny eco-saboteurs – maybe the actual inspiration for this Operation title.)

The plan involved a Predator drone – geez!

And three law enforcement snipers on call!

Here’s the security team’s goofy ass Star Wars call signs

Source: Operation Point Break

A note to readers: For the episode and for the print version of this project, I asked Energy Transfer about all this stuff. They didn't provide answers to those questions.

Further reading on sacred sites: Valerie Grussing, executive director of the National Association of Historic Preservation Officers, encouraged me to check out this amicus brief they filed with a bunch of orgs and tribes in this super important Supreme Court case attempting to stop construction of mine by Resolution Copper on a site sacred to Apache people called Oak Flat. The court ruled against Apache Stronghold last spring, and Trump has unsurprisingly indicated he will allow the mine to go ahead. You can learn more about the fight for Oak Flat by checking out Indian Country Today's archives.

To dig into the documents further: You can find all the documents that informed SLAPP'd here, organized by episode.

The entire SLAPP'd series is here – minus the finale, which will be out very soon. You can also listen to it wherever you find podcasts, if you search Drilled and go to Season 12.

To Support my work, consider a paid subscription, and thank you!!

Member discussion