My Latest: Pipeline company orders tear gas, radios for police

TL/DR: I wrote a new article, and you can read it at Grist or at The Intercept.

For almost exactly six years now, I've been covering one story: how an oil pipeline company collaborated with law enforcement to quell the Indigenous-led movement to halt the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock. Recently, there was a big break in the story.

In 2020, when I was a staff reporter at The Intercept, I filed a massive public records request, for thousands of pages of internal documents the private security company TigerSwan — which was hired to protect the pipeline — had turned over to the state of North Dakota. I only just started receiving them.

A lot happened in between. For one, The Intercept laid me off, and I entered the harsh world of freelance reporting. Their former parent company First Look, however, continued to fight in court against the pipeline parent company Energy Transfer to get me the documents. Energy Transfer really, really didn't want me to have them — the fight made it all the way up to the North Dakota Supreme Court. We won.

So this spring, I reunited with my ex-bosses to do a first pass at over 55,000 pages of emails, PowerPoint presentations, and WhatsApp chats documenting in detail the strategies this company used to confront one of the important environmental and Indigenous uprisings of our generation. I was worried that there wouldn't be much there. I was wrong.

Today The Intercept and Grist published my second article about the records (the first one is here, and this is actually Part 19 of my absurdly long Intercept series Oil and Water) — cowritten with the brilliant investigative journalist Naveena Sadasivam, who you should follow. Newsroom developer Akil Harris made the documents navigable, researcher/icon Margot Williams tracked down phone numbers, and old friends Ali Gharib and John Thomason edited.

I'd strongly encourage you to read the story in full at Grist or The Intercept. And that might be enough for you. However, to me, the documents themselves are what's so fascinating about this story.

So this part's for the nerds. I'm going to hold your hand and take you through some of the wild twists and turns in these documents.

This article was all about TigerSwan's collaboration with law enforcement — both on the ground, as sheriffs' deputies confronted people protesting — and in the realm of propaganda. However for this post, I'm just going to focus on the on-the-ground collaboration. I'll get into the propaganda part in a follow-up.

But before we get into it, let's briefly address one question: Why do we care if law enforcement worked with a private security company to respond to massive protests?

Here's how I think about it: The climate crisis is one of the biggest public health issues we are facing today. Without a rapid shift away from fossil fuels, we will face increasingly unmanageable storms, wildfires, heat, and floods. No one will be spared, and suffering will increase across the board — but the impacts will be most dire for the most vulnerable among us.

Fossil fuel corporations exist to make money. That's how capitalism works — the point of these companies is to make as much money as possible on a product that has historically been one of the most lucrative. Facing a crisis that could eliminate the money-making power of their product, fossil fuel companies turn to an array of tactics to continue to produce. There are "soft" tactics, like PR companies attempting to influence the public by planting pro-pipeline articles. And there are "hard" tactics, like the threat of armed force. Winning the hearts and minds of the public is at least as important as physically guarding oil and gas infrastructure.

When fossil fuel companies have law enforcement on their side, it not only means access to armed forces with the power to incarcerate people — but it also tells a story. It aligns fossil fuel production with stability and law and order, and aligns anyone who is against the fossil fuel industry with criminality. It strengthens the power of an industry that is causing an immense loss of life and biodiversity.

Police have a huge amount of discretion to respond to perceived threats as they see fit. In the fairytale version, cops are neutral arbiters of justice, biased only toward the law. How does that shift, when police are placed in between a corporation that offers them money, friendship, and collaboration, on one side, and, on the other, an uprising of people who feel that "law and order" has failed them?

Below are a few of the examples we uncovered of law enforcement working with the pipeline company. There are many more in the full Oil and Water series.

Example 1: TigerSwan buys radios intended for law enforcement

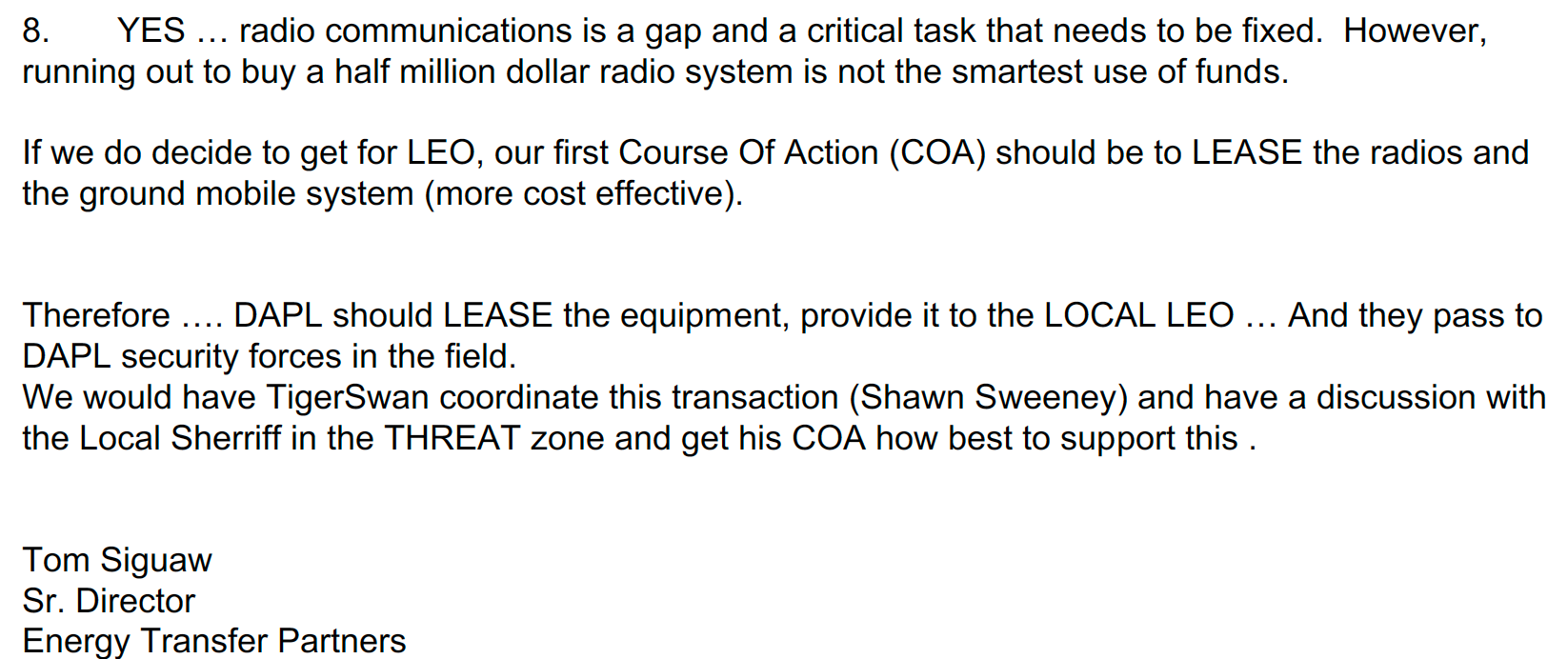

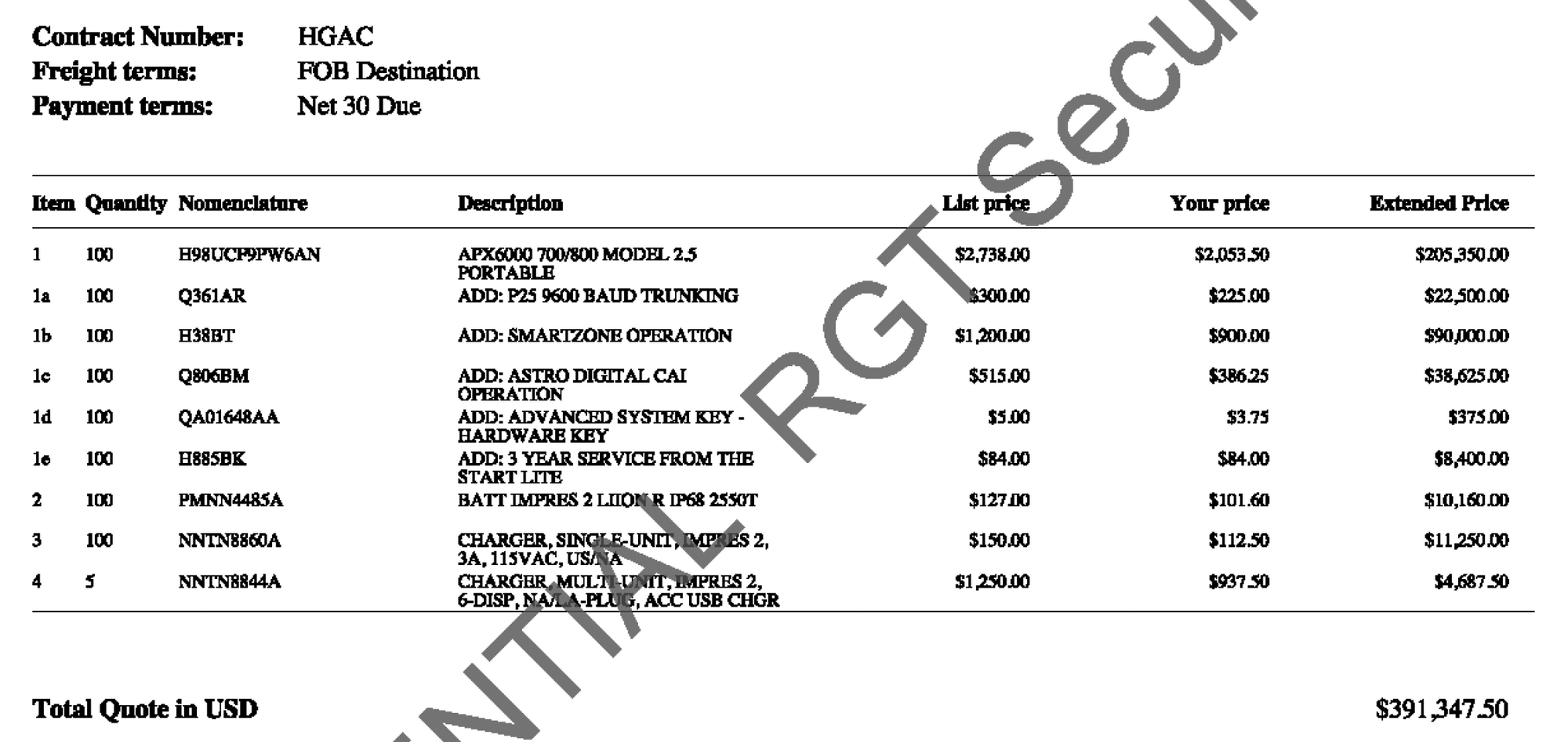

Energy Transfer purchased $391,347 worth of radios in September 2016 with plans to lease a number of them to law enforcement officers. They hoped the radios "would allow security forces to have comprehensive knowledge of ongoing tactical communication during operations."

This kind of "gift" to law enforcement would represent "DAPL’s concern for public safety."

Eventually, they settled on leasing the radios (though they would still be coded as a gift for accounting purposes.)

Total bill: $391,347.50

Example 2: TigerSwan creates shared drives for police and private security to exchange evidence

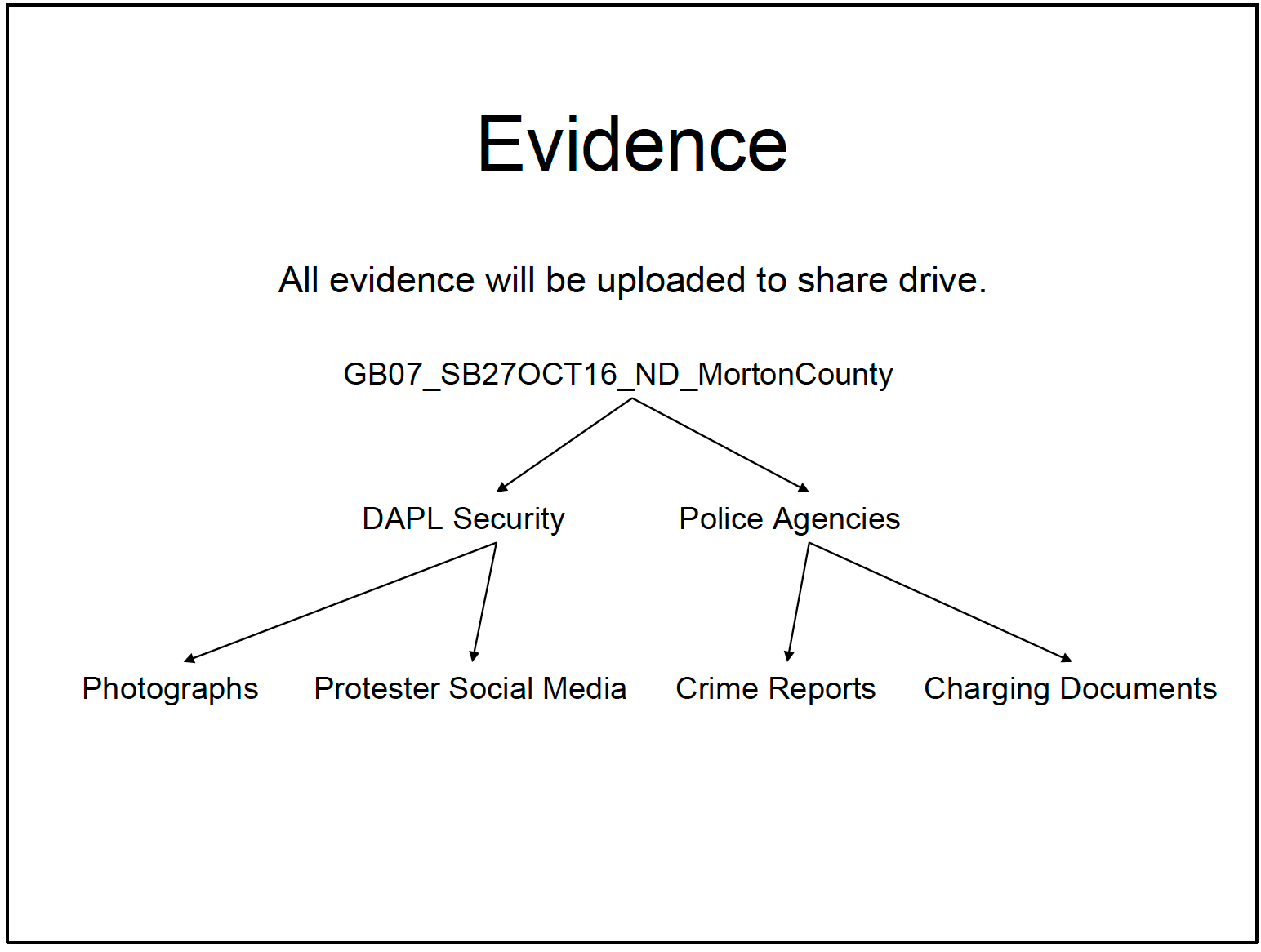

The documents make it clear that TigerSwan hoped to gather evidence that law enforcement could use to prosecute water protectors.

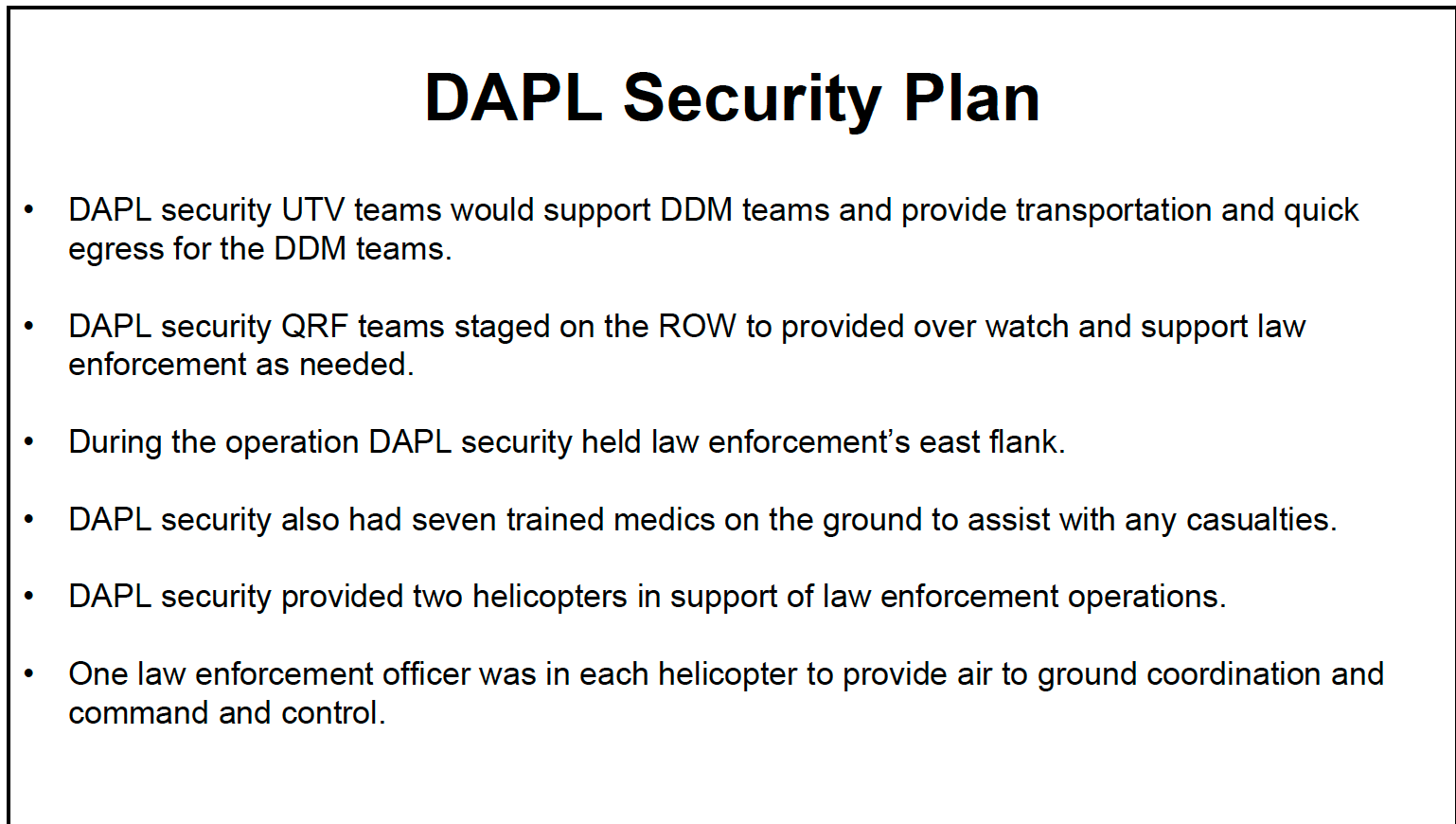

On October 27, 2016 — the day of the largest mass arrest of the movement — private security collaborated extensively with law enforcement, according to a document I received.

At the end of the day, they planned to create a shared drive for "evidence."

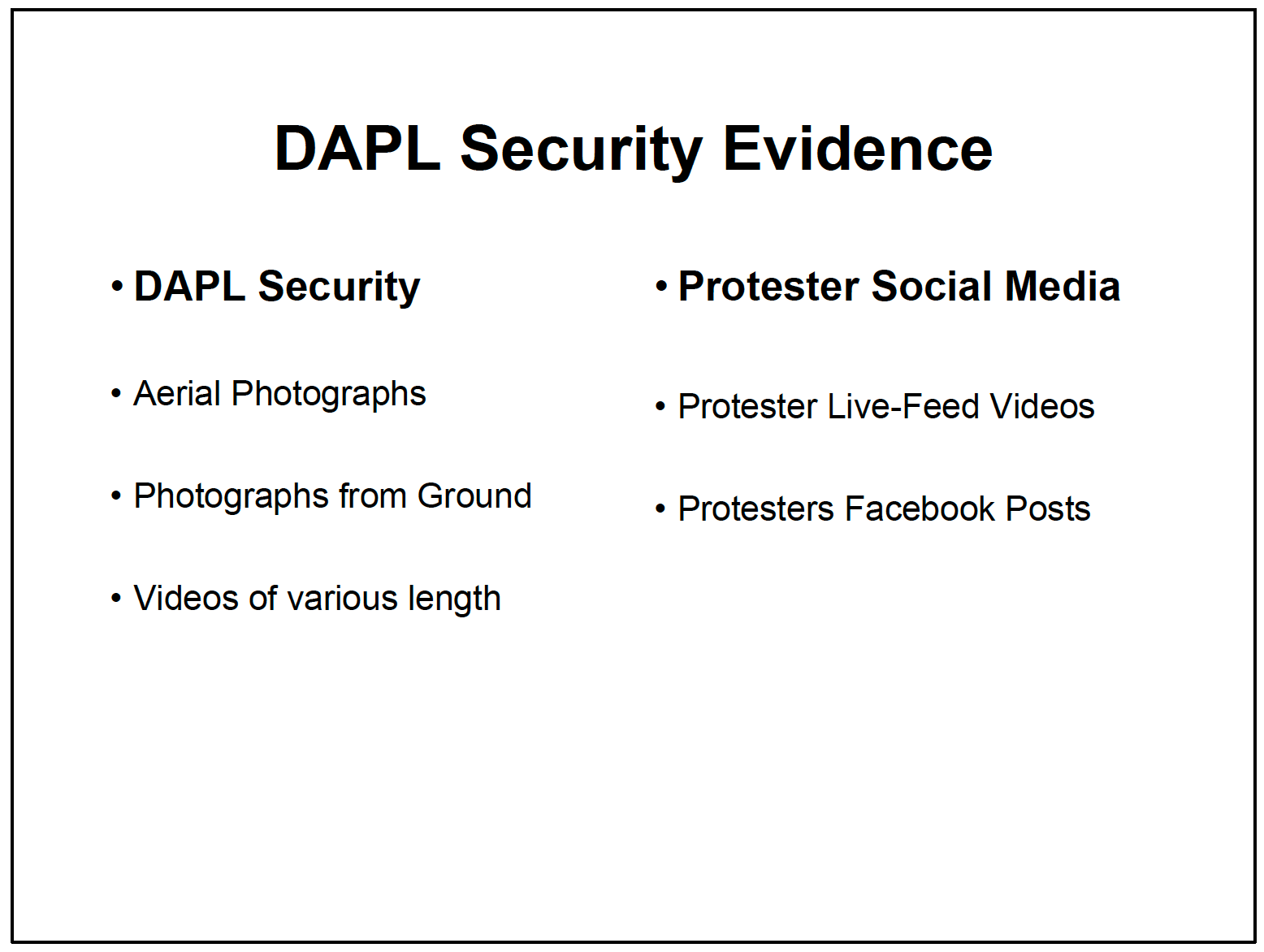

DAPL security had been taking photos and videos, from inside helicopters and from on the ground. They were also closely following social media. All that intelligence would go to law enforcement.

They created another drive like this in February 2017, a document shows.

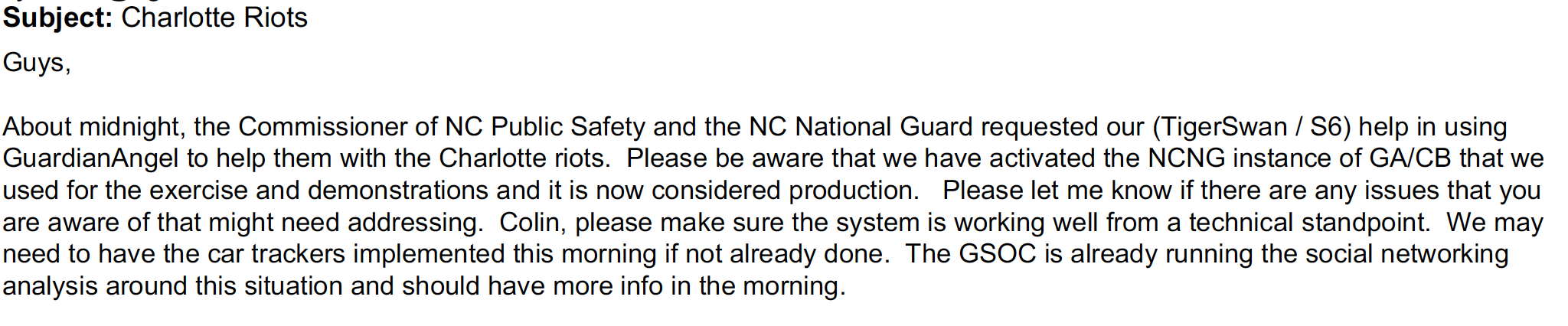

Side Note: At the same time that the Standing Rock movement was gaining steam, in September 2016, TigerSwan was hired to help law enforcement confront another social movement uprising, in Charlotte, North Carolina, in the aftermath of the 2016police killing of Keith Scott.

This is relevant to the next part, you'll see.

Example 3: TigerSwan attempts to purchase less lethal weapons for police

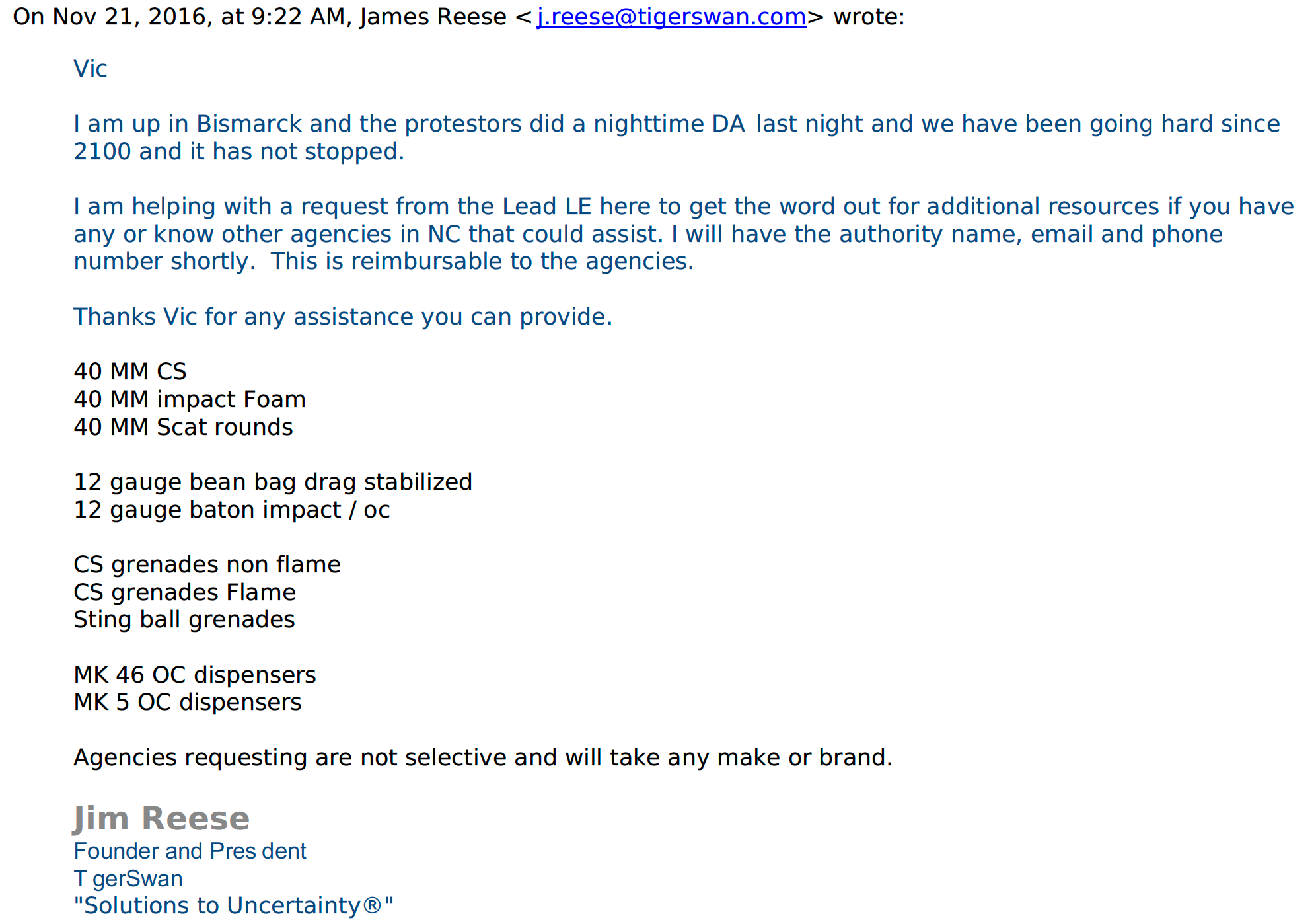

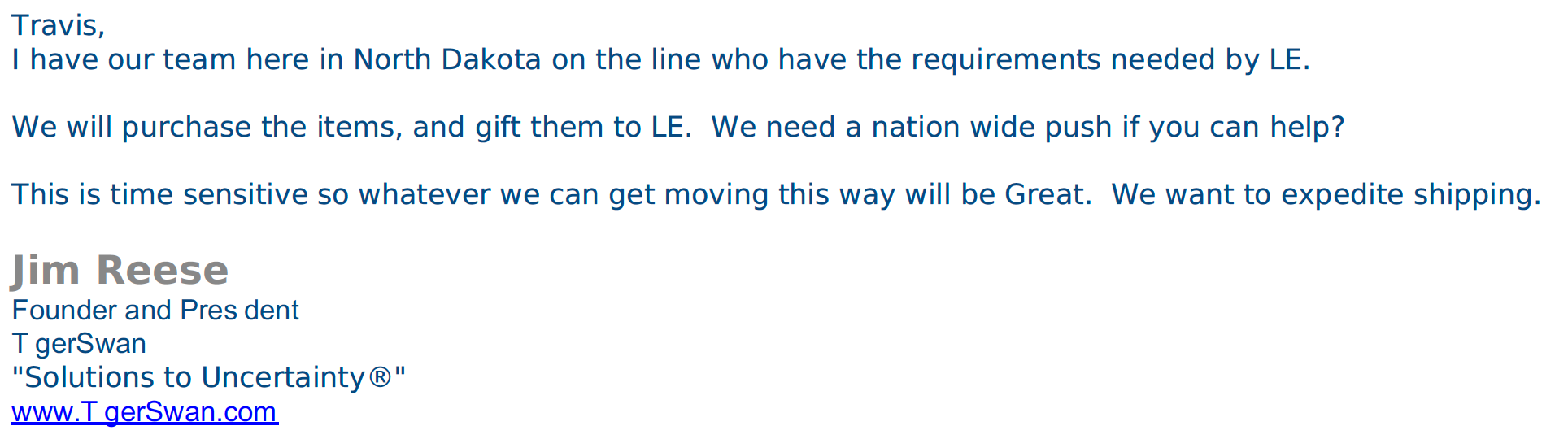

November 20, 2016 was one of the most notorious nights of the Standing Rock movement. Law enforcement sprayed water hoses on pipeline opponents in bitterly cold weather, with below-freezing temperatures. In the morning, law enforcement was running low on so-called less lethal weapons. TigerSwan founder James Reese — former commander of the elite Delta Forces Army unit — stepped in, reaching out to an old contact from the military, who had also been working in the North Carolina fusion center during the Charlotte uprisings.

Reese's contact referred him to the manufacturer Safariland.

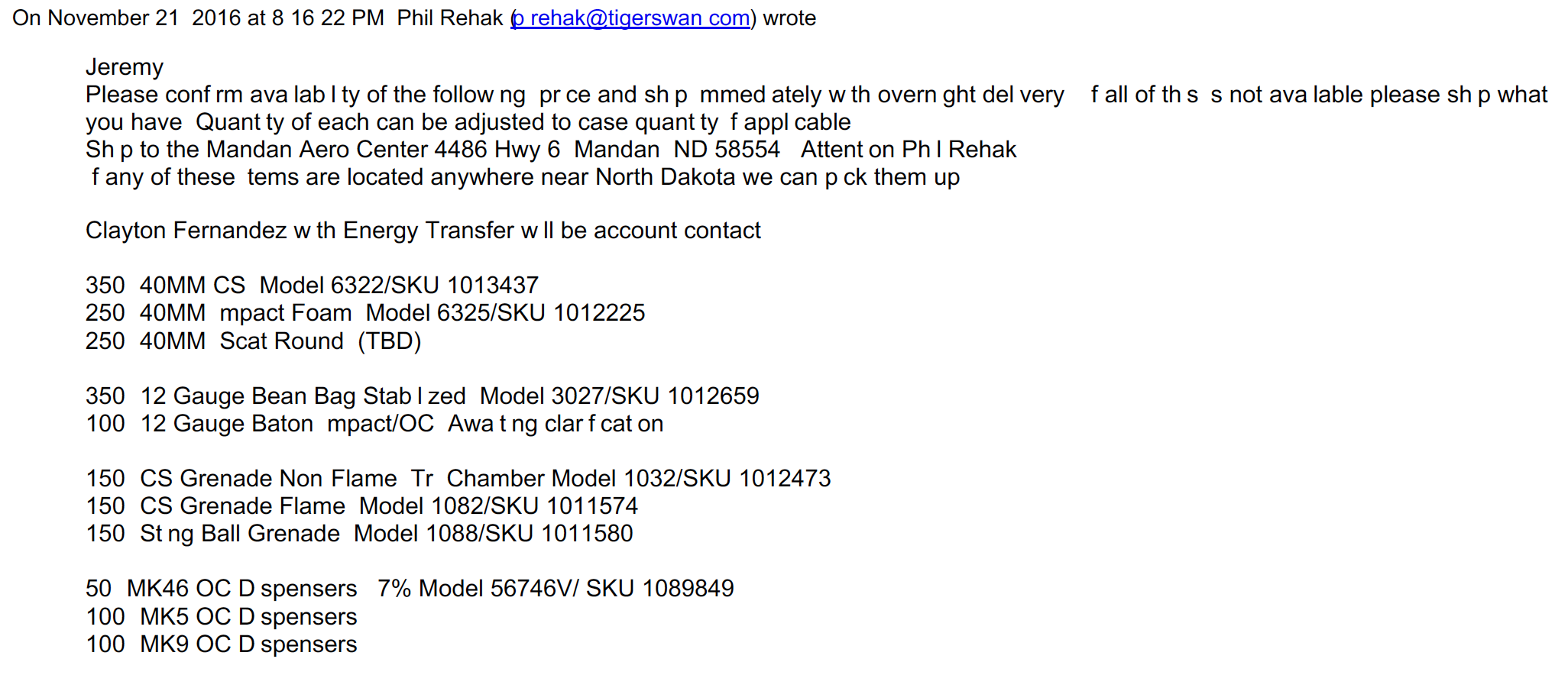

At the same time, another TigerSwan contractor, Phil Rehak, reached out to contacts at the law enforcement equipment vendor Streicher's. He had an even longer list of less lethals.

I spoke to that contractor, Phil Rehak. He told me, “I would be given an order by either somebody from TigerSwan or maybe even law enforcement, being like, ‘Hey, can you find these supplies?’”

Example 4: TigerSwan hires a cop

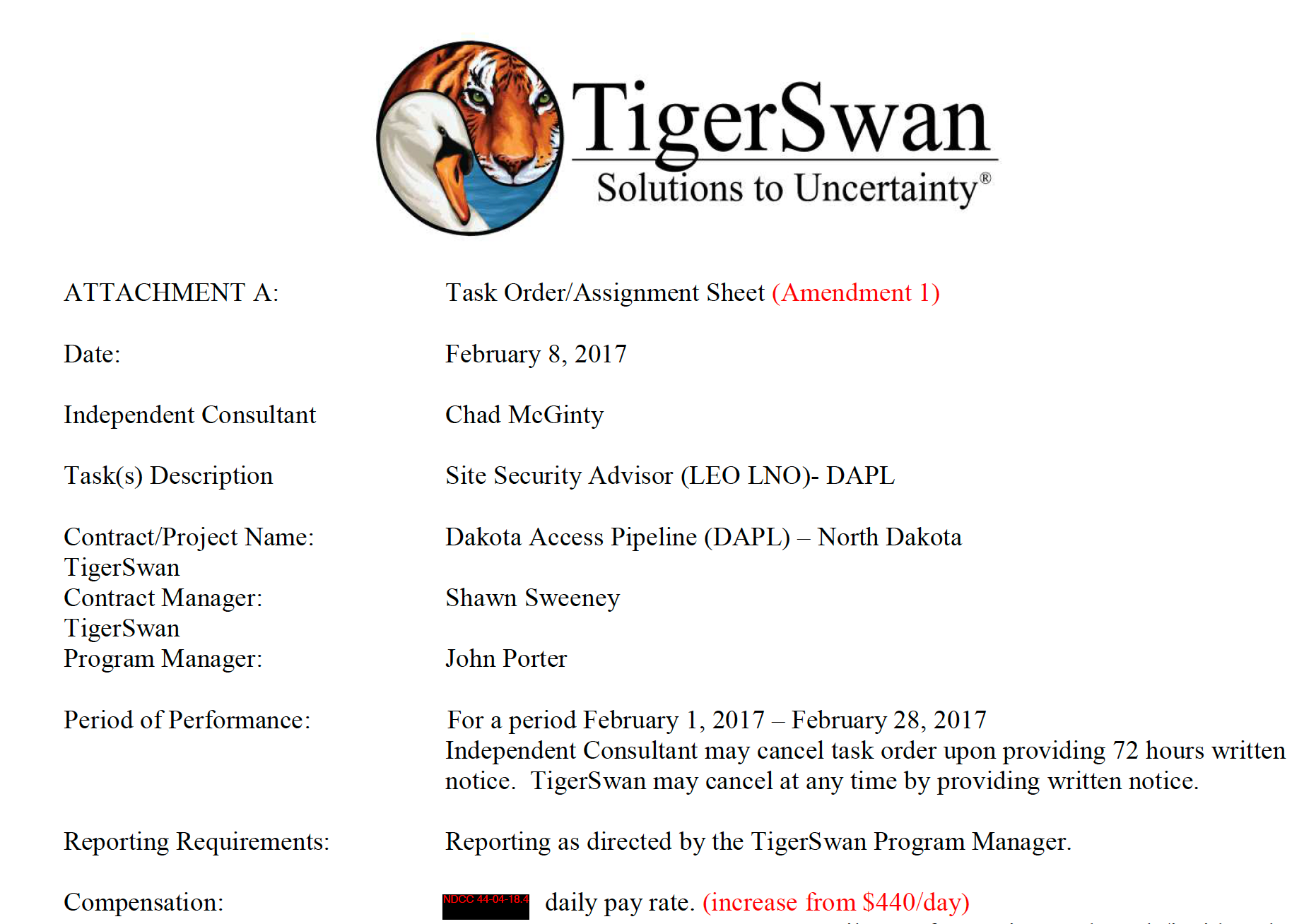

Throughout the Standing Rock protests, law enforcement officers from around the Midwest joined local police to confront a movement that was thousands-strong. Ohio State Patrol Maj. Chad McGinty was one of them, serving as commander of a team from the state in November 2016. By February 2017, after a series of emails from senior TigerSwan executives, McGinty was a law enforcement liaison working for TigerSwan at more than $440 per day.

For other examples of police / fossil fuel industry collaborations, check out some of my other reporting:

Member discussion